Trickle-Down Epistemology

It’s been too hot lately for soup, so instead I’ve been thinking about epistemology. As in, there’s a lot of people worried about AI’s potential effect on our ability to comprehend reality. This concern is only newish: Deepfakes have been around since 2017, and at the time a major concern was that no one would be able to distinguish real from fake images anymore. The internet would soon be awash in AI-generated political propaganda, celebrity nudes, and “proof” of UFO’s and conspiracy theories, confusing the hell out of the average person.

More recently, chatbot driven AI psychosis has been in the news. Some models have a tendency to flatter users and tell them whatever they want to hear, even when the users have clearly gone bananas. This has led to many anecdotes of previously normal people having their pet ideas reinforced and elaborated by chatbots to the point where they now believe they are the messiah, or that the AI is some kind of sentient god.

Further, even the most advanced AI’s are still prone to frequent hallucinations (a sentence that would have sounded like a bad sci-fi plot five years ago). In situations of uncertainty, they will make up plausible sounding but fake information, or cite fictitious sources. Sometimes they will pretend to have access to information they don’t, helpfully summarizing a book they haven’t read or that doesn’t exist.

But, at least so far, none of this has been a particularly big problem for societal epistemology. Fears that all political discourse would be derailed by literal fake images have turned out to be overblown. AI psychosis is a real and disturbing trend, but back-of-the-envelope estimates imply that it affects only 1 in 10,000 people, making it about 50x less common than schizophrenia. There have been some widely publicized cases of e.g. lawyers leaving AI hallucinations in court filings, but this feels more like people not knowing how to turn the cat filter off on Zoom than it does a reality-fraying crisis for the legal profession.

All of these things might be a larger problem in the future. But I fear we’re forgetting that we still haven’t really reckoned with our previous epistemological disaster: The internet. It’s hard to imagine now, but at the dawn of the web most people were optimistic that the widespread availability of information would make the average person more informed and more rational, improving the quality of our public discourse and our democracy. Few to no people think this now, so let’s ask the question: What went wrong?

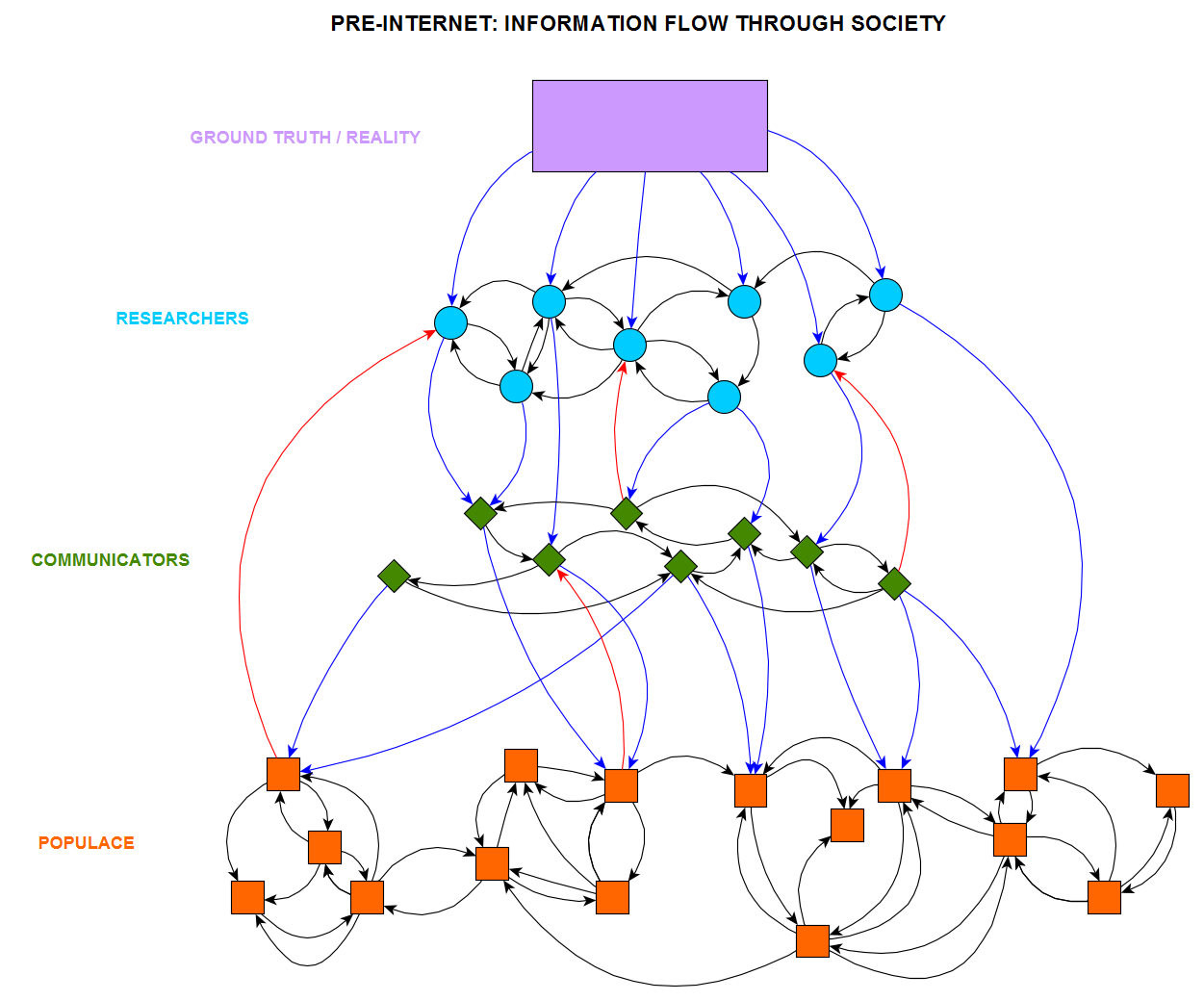

Plausibly the answer lies in the sudden and enormous changes the internet imposed on the structure of our social graph, the network of information flow through society. This graph wasn’t exactly static prior to the internet, but it was a fairly slow-changing network of informational connections based largely on either in-person interactions or broadcast media. Information was generally transmitted via centralized media sources (newspapers, radio, TV) and was relayed outward towards the informational peripheries:

In the toy model above, nodes in the graph represent people, and arrows represent the flow of information. People here are divided into three broad groups: Researchers, communicators, and the populace. These groups differ with respect to their relationship with information: Researchers (think scientists or historians) are the people who collect or refine new knowledge. Communicators (think teachers or journalists) parse and transmit this information. And the populace is everyone not primarily engaged in the creation or transmission of information (think nurses or plumbers). Blue arrows are down-links, information flowing from a higher level to a lower level. Red arrows are up-links, from lower to higher, and black arrows are side-links, representing information flow within a level.

Some disclaimers on the model: I am aware that this is overly simplistic and that in reality there isn’t a literal hierarchy with clean breaks between layers. Scientists can and do write books for popular audiences. An investigative journalist is part researcher and part communicator. Perhaps a random member of the populace might craft novel soup recipes, and thus in some sense be a researcher. Anyone might be a member of any layer in some facet of their life. Still, I am going to handwave and say that something like this sort of represents information flow in the pre-internet society, so we can get on with the fun part: analyzing graph structure.

In this graph, most information flow is either within layer, or flows from a higher layer to a lower one. Researchers investigate “ground truth”, with information flowing from reality down to them. There is a lot of information flow between researchers as they compare and criticize each other’s ideas. Then there is information flow from researchers to communicators, who in turn have many side-links as they share information with each other. The communicators transmit information to the populace, and the populace primarily communicates with other members of the populace (that are geographically nearby).

Of course, even prior to the internet, information flow was more complicated than this neat story. There was some flow from the populace up to communicators and from communicators up to researchers, as well as some flow directly between researchers and the populace. It’s not depicted here, but everyone has at least some access to ground truth. But still, there is something like an information pseudo-hierarchy here, and the graph structure promotes a constraint on information that I think of as “trickle-down epistemology”.

That is: Much of the information that people receive has a total path in the graph back to the ground truth, and it was mostly relayed via nodes that had standards for what information they transmit. A random member of the populace had probably heard, for example, that there was a hole in the ozone layer, and that it was a problem, and that aerosol sprays were somehow to blame. They didn’t determine this themselves: They read about it in a newspaper, or heard about it from someone else who had. The newspaper writer got their information by interviewing a scientist about it, and the scientist got the information from direct experimentation.

This paradigm certainly wasn’t perfect. First of all, the researcher could have been wrong, and then everyone down the chain would be receiving wrong information. Further, at each link in the graph, the information can lose fidelity or be modified by the person transmitting it. Perhaps people who read about the ozone hole in the newspaper didn’t understand it and explained it wrong to their friends. Maybe the article didn’t even explain it correctly. But the graph of information flow at least gives the populace some assurance that information that reaches them mostly originated in reality, and was mostly transmitted to them by people who knew what they were talking about.

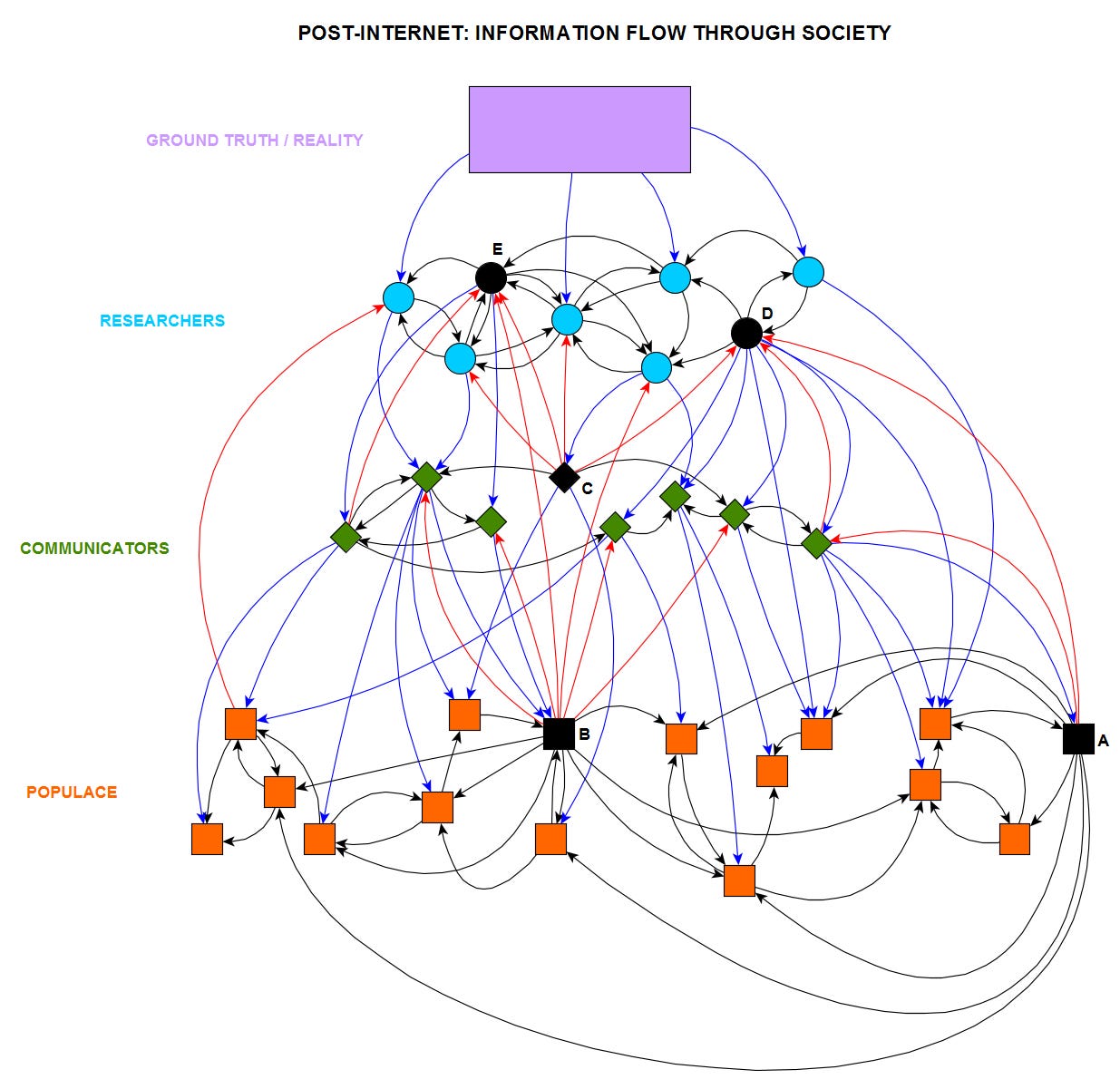

Now let us consider the way the graph changes after the internet and social media are available. These are the same nodes as before, but with different connections:

The first thing to notice about this new graph is that there are more total links, representing a real increase in the total amount of information flow. The internet made communication cheaper, so many new interactions occur that just wouldn’t have happened before (imagine a modern youtuber having to mail videotapes of their posts to subscribers).

There are also more red and blue links between the layers. We’re still showing the layers as distinct, but in fact they are much less so than in the previous graph. Members of the populace are receiving more information from communicators, but they’re also sending more information back (e.g., by arguing with them on twitter or in comments sections). Researchers are also communicating more directly with the public, and are more likely to hear back from them.

If you look at the populace level, geographic distinctions are flattening. Whereas previously most communication was between pseudo-cliques of people living near each other, now increasing amounts of information is flowing between these cliques to more distant areas. This also means that there are fewer local links between the populace, with more of their information coming from people farther away or from higher levels of the graph.

So far none of this is obviously bad. Maybe people are missing out on some in-person connections or local news, but they could be learning a lot by hearing more from people in distant places, or by reading more from various communicators and researchers. Journalists and scientists could potentially benefit from hearing more feedback from the public.

But if we zoom in on some individual nodes, we’ll start to see some concerns. Node A (bottom right) has a large out-degree (information going out) but a very low in-degree (information coming in). This person has become a sort of “influencer”: Despite not receiving much information themselves, they can now use the broadcast abilities of the internet to cheaply publish their content online. It is of course possible that this person is a lone genius, but they might just as easily be a conspiracy theorist.

Node B is also an aspiring influencer, with new side and up-links. They at least have more information coming in from various sources. Still, they are acting like a communicator, but potentially without the fact-checking standards or reputational stakes that come with being a professional journalist or educator. They cannot be fired for making egregious mistakes. In cases of anonymity they might not even be able to be blamed for them. Such a person might be spreading information in a beneficial way, but they might not.

Node C has become a kind of thought leader: A popular communicator that is widely read by both the populace and by researchers. Again, this could be very useful. But it also might be the case that this non-expert is so good at communicating (in some domain) that their content supplants that of experts who actually understand the subject matter better.

At the researcher level, nodes D and E have increased their total number of links, both within the researcher community, and with communicators and the populace. But they have done so at the expense of their links to ground truth, i.e., they no longer have time to do direct research. Even this isn’t provably bad: There were always some researchers who didn’t directly investigate reality, but merely synthesized information from other researchers. But you might worry in these new cases that they’re getting farther away from the ground truth, and might be spending all their time defending their existing opinions without examining any new evidence.

There are also some new structural problems unrelated to any particular node.

Because of the increase in total links, and especially because of the increase in up-links, there are more and longer information flow loops in the system. This means that information that reaches any particular node, even if it did begin in ground truth, possibly did so through a much longer total path. This is also not necessarily bad. At each node in the graph, information can theoretically be either degraded or improved before being passed on. And it was always possible to have arbitrarily long information pathways even in the pre-internet graph, although loops were more likely to have been within-level. Still, now with longer informational chains that are also more likely to repeatedly cross layers, you could be suspicious that more is being lost than gained here.

Also due to increased connectivity, information that was previously somewhat compartmentalized is going through a process of de-compartmentalization. Sometimes this is good: Some researcher somewhere probably already had an estimate of how prevalent sexual assault was, but it took the internet-enabled #metoo movement to make such information common knowledge. Similarly, various types of institutional dysfunction are more apparent to the public now than they were when it was easier to keep embarrassing information under wraps.

But some things were compartmentalized for a reason. Previously internal academic debates are spilling out into distant parts of the graph, potentially derailing discourse. If philosophers or policymakers want to seriously discuss a sensitive topic, they now have to fear this being picked up on social media and endlessly misconstrued based on out-of-context audio clips, to which they will feel forced to respond, and so on. Meanwhile, events that previously would have been a local news story can go viral and receive global coverage, with the unwanted attention often massively disrupting people’s lives. Members of the public are also increasingly expected to have detailed opinions about debates regarding highly publicized political or social issues, even when they have no expertise or even interest in that subject.

Finally, each node (person) has a limited amount of information they can consume (i.e., a maximum in-degree). In the pre-internet graph, nodes were farther from being information-saturated. Back then, people were capable of consuming more information, but it wasn’t easily available to them. In the modern graph, nodes are closer to information saturation, meaning the opposite is true for them: There is more cheap information available, but they are already near the maximum of what they can consume. Under these conditions, information has to “compete” for attention to a degree that it didn’t before.

Between the de-compartmentalization, longer information paths, and higher competitiveness for information, a new dynamic arises. The graph has become an evolutionary environment that puts selective pressure on information to be the right kind of information. In order to survive and propagate, information has to be a good meme. Accuracy and logical coherence are still positive memetic traits, but they are increasingly competing with other qualities like outrageousness, surprise, humor, simplicity, shareability, actionability, and sexiness. Some information that originated in ground truth is no longer attentionally grabby enough to survive and propagate through much of the graph. Worse, information that didn’t originate in ground truth, or was substantially modified somewhere in the middle of the graph, now is the right kind of meme to replicate its way through the nodes.

Under these conditions I worry that we’re moving from our trickle-down epistemology paradigm to something more like “memetically-evolved epistemology”. And while there was always a memetic component to culture, it was previously tempered to a larger degree by information flowing from reality. In the hyperconnected and more saturated modern network, evolutionary pressures operate over longer paths and larger areas of the graph, giving information the time and space to mutate into memes that are highly effective at spreading. In this new paradigm, unsexy information which happens to be true is often at a competitive disadvantage.

Most of these aren’t exactly novel concerns. Almost everyone is aware by now of problems caused by internet filter bubbles, social media attention hacking, conspiracy theory rabbit holes, clickbait, ragebait, etc. But most critical discourse on these issues focuses on blaming big tech companies and their evil algorithms. My purpose here is to emphasize that much of the societal and epistemological disruption caused by the internet is inherent to the way it restructured our informational graph. This would have caused major problems even if we were lucky enough to have non-evil tech companies with good algorithms.

Prior to the internet, it was natural to imagine that more communication was always better. In reality, we are now in a world where roughly 10% of Americans think the Earth is flat, or that vaccines “implant a microchip”, with younger people even more likely to believe such things. Depression and anxiety are up. Attention spans are down. In a hard-to-articulate way many people seem to have lost cognitive agency, their attention being batted from one meme to another by the network, with little conscious intent on their part.

Maybe all this shouldn’t have been so surprising. Imagine we were to radically increase the number of connections between neurons in a human brain, holding the number of neurons constant, but massively connecting areas that were previously distinct regions. I’m not sure exactly what would happen, but you wouldn’t predict this would improve the functioning of the organism. If it would, why didn’t evolution do that in the first place?

The pre-internet information graph wasn’t perfect and it didn’t arrive to us fully formed, but over time it had reached an equilibrium that was compatible with society more-or-less functioning. Links in the graph that tended to provide false, harmful, or irrelevant information were selectively pruned based on the judgments of the people they connected. But that process is slow and technological change is much faster now. It’s unclear if we’ll be able to keep up.

I’m not saying the internet is all bad, or that it will always be a net-bad. There are surely some people who are using it “well”, for whom it is beneficial to their understanding of reality. We’ve had social media for ~20 years and in this time we have learned to adjust a few connections in the graph, pruning some and promoting others. Community notes and volunteer moderators have the ability to correct or remove some of the more blatant misinformation from spreading. Wikipedia still seems to work somehow. It’s not necessarily hopeless.

But as we enter the AI era, I want us to remember that, far from having a forward-looking plan to deal with the next reality-warping technology, we are still reeling from the previous blow dealt to our epistemology by the internet.

Then again, maybe you shouldn’t listen to me. I’m just node A, after all.